video editor: Mohammad Irshad Alam

British historian Kim speaks with a wagon, who is visiting the ongoing Zee Jaipur Sahitya Festival, The QuintNishtha Gautam about his book Amritsar 1919: A Empire of Fear and the Making of a MassacreNationalism in the present India, and Kohinoor.

What is your version of what happened in Amritsar, because Indians see it very emotionally.

I have tried to move away from highly political context, either a version that is somewhat indifferent about the empire or about the magnificent works of people like Udham Singh and Bhagat Singh. If you go to Amritsar, it is a very high outline in which it is painted. So I try to retreat and peel some of those layers and see what the primary material said at that time and see if I can write a type of history from more balanced and fine fashion.

Do you think your book is going to make an alternative story that we have in India?

I really have no aspiration beyond providing a different story. In fact, on April 13, the kind of political speeches given in Jalianwala Bagh, which we have, talk about the government. For example, Jalianwala Bagh has a martyr’s well and sign says that the bodies of 120 people were taken out of the well, but there is no historical evidence for it. And I am trying to be as sensitive as possible in case of not humiliating people’s sensitivity, but at the same time if there is no historical evidence, then I have to conclude that this did not happen.

You have mentioned in your book that the decision to open the fire of General Dyer was out of fear.

Illustration of General Dyer in Gandhi The film is to face a type of stone, which is almost a caricature of a colonial officer, who is under complete control over his feelings and works out of some kind of callus blood thirst. And this simply does not help us understand that violence is embedded in a person. And as we can tell from many different accounts that Dyer gave, he did not experience a peaceful crowd in front of him. It was a peaceful crowd but felt that he was rebel. His entire view for what he was doing in Amritsar was a state of war. He worked on calculations that were frightened and the misconception of the situation and were wrongly based.

How do you compare the situation in Kashmir with a modern day situation, where protests sometimes become violent and security forces resort to using arms that cause serious physical damage to protesters?

I try to avoid much comparison with current events, but it is quite clear that you have such skirmishes that took place in West Asia as well. You can see that the argument of violence implemented by state forces follows a very similar pattern. Which is often about exemplary violence. To some extent, it really does not matter who hurts, as it sends a clear message that the authorities are ready to take what is necessary to reduce the disorder. Therefore, there is a very clear element of collective, but there is also no very intelligent violence.

What is your assessment of nationalism in the present India?

I think Modi inaugurated a new museum at Red Fort, with 1857 and Jalianwala Bagh and Subhash Chandra Bose and I am eager to see what those performances are. But you can see that there is a reconstruction of India’s past which has converted into an essential political project, which is a memory. And the entire panthian of national heroes, which goes back to the Queen of Jhansi, Mangal Pandey, which is used for different purposes in various contexts. It crystals special political messages, and then they incarnate them in people.

What will be your last message through this book about the history of Indian freedom struggle because we Indians understand it?

I believe that no one has the right to history, at least it is what I keep telling myself as an academic. I am not asking people to accept everything I say, but be open to the chances of looking at things with at least a different perspective. And now that the call of forgiveness for Amritsar massacre at this time increases, I think people can make at least some efforts or open to see what happened on a deep level.

Is forgiveness coming on everyone?

Forgiveness from an Indian point of view will be understood only when the Amritsar massacre is seen as a symbol of oppression of British rule. And a British government would only apologize by saying that it is not a representative of the British government, that it was just a ‘rotten apple’, that General Dyer was a rose officer. And that the massacre somehow reflects British rule.

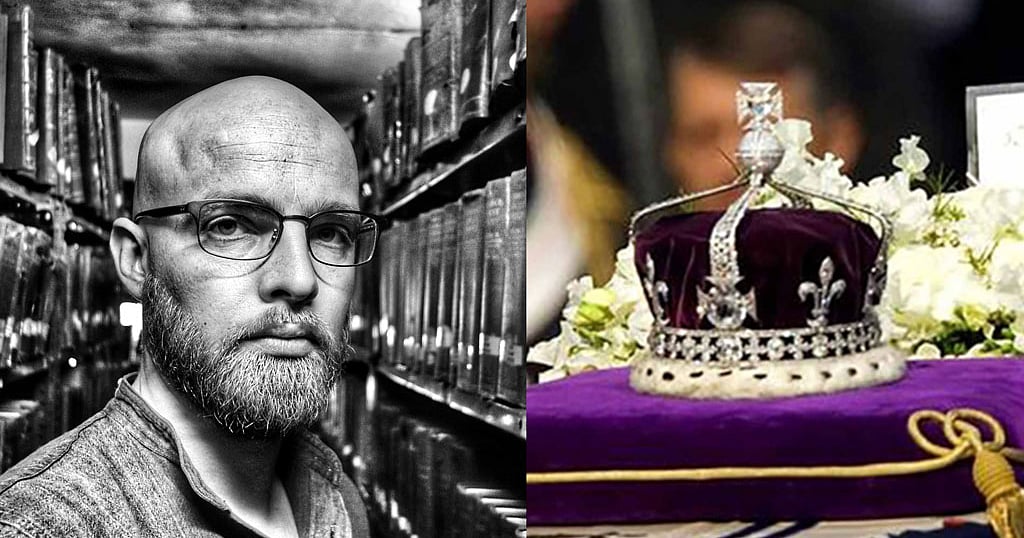

Asked if all will be with forgiveness with the return of art work such as Kohinoor’s return, Wagner said that the return of real objects is not as important as the debate about the legacy of the empire. This, for him, is far more valuable in terms of establishing more fine and complex appreciation of the past.

Published: