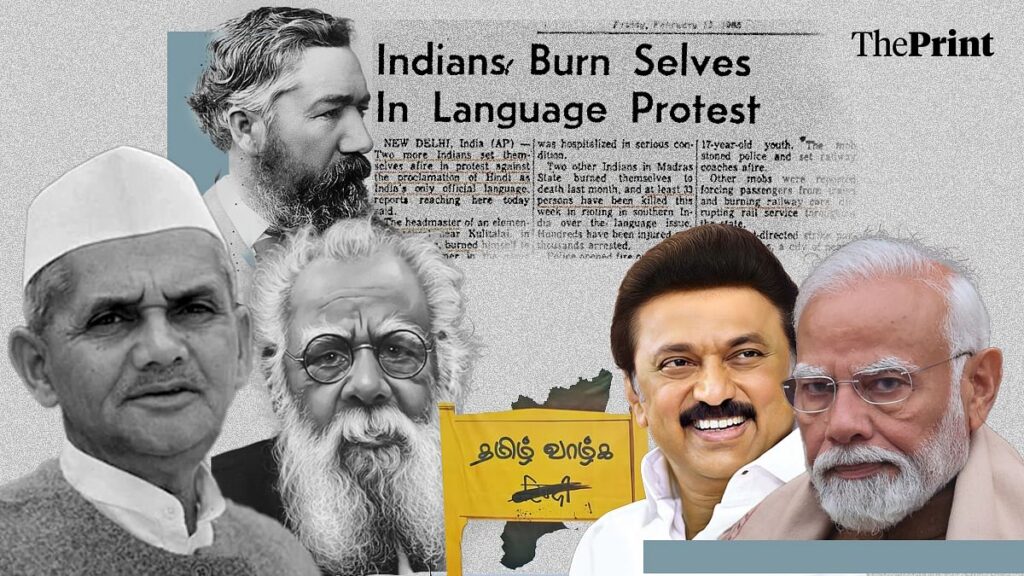

At the break of dawn the next day, Chinnasamy walked out of his home, leaving behind his ageing mother, a young wife, and an infant daughter, and reached Tiruchirapalli’s railway station with a can of petrol. He then proceeded to empty the can on his body and set himself ablaze. His last words: “Inti olika! Tamil valka! (Down with Hindi! Long live Tamil!).”

For the next few months, there was utter pandemonium in the state; 1965, the year after which Hindi was set to become the sole official language of India, was fast approaching. In December 1964, then-Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri stated in a speech at Bengal’s Shantiniketan that retaining English as the official language for all time “seems to me a deeply humiliating proposition”.

Madras went up in flames. Dozens died by suicide or in riots. Hundreds went behind bars. Classes in schools and universities remained suspended indefinitely. Looking at Tamil Nadu at the time, US political analyst Selig Harrison’s ominous prediction of India splitting up into “a number of totalitarian small nationalities” did not seem too far-fetched.

Indian media up North, much like its Western counterpart, was confused, disgusted and dismissive of what it saw as “fanaticism” and “frenzy” that it had typically come to associate with Tamil speakers.

Decades after the protests of the 1960s, the language question has become dominant, once again, in Tamil Nadu. Chief Minister M.K. Stalin recently urged Tamilians to rise against “Hindi imposition”—in the backdrop of the Centre’s move to impose the three-language policy in place of the state’s two-language policy—just like the Tamil leadership six decades ago. In the recently concluded session of Parliament, the MPs of the ruling Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) protested against the Centre by wearing black outfits.

While Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman kicked up a storm by stating in the Parliament that the DMK revered the person who once called Tamil “a barbaric language”, in a reference to Periyar, the Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister jumped into the debate, with a question. Since Tamil was “as ancient as Sanskrit”, why love for the language should evoke hate against Hindi, he asked.

On his visit to Tamil Nadu Sunday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi also took what appeared to be a dig at Stalin over his signature, which, the PM said, was not in Tamil.

As the cloud of “language politics” looms over the Tamil Nadu-Centre relations again, ThePrint explains how and why the Tamil language became the cornerstone of modern Tamil identity; if indeed, as Adityanath suggested, love for Tamil tended to evoke “hate” for Hindi; whether, a figure such as Periyar, who opposed North Indian domination all his life, saw Tamil as a “barbaric language”; and how, in recent years, the BJP’s discursive ascent in Tamil Nadu has brought to the fore its people’s entrenched apprehensions about language, identity and their place in the Indian nation.

The Genesis: Arrival of Brahmins

The schism between Sanskrit and Tamil goes back at least a thousand years, said G. Balachandran, former IAS officer of the West Bengal cadre and Delhi Tamil Sangam’s ex-president.

“When, during the Chola period, the influx of Brahmins [brought to South India from Rajasthan by King Rajendra Chola] multiplied their numbers in the region, they [the Brahmins] made several legislations to further protect themselves on an alien land. For instance, adding to the already enforced law that even if a Brahmin committed murder, he could not be punished with the death sentence, more such laws, preferential to the Brahmins, became the law of the day,” Balachandran said. “Even Raja [king] Raja Chola could only banish the murderers of his elder brother, Crown Prince Aditya Karikala. He could not give them the death sentence since they were Brahmins,” he added.

“The Brahmins also made Sanskrit the official language of the temples—something that, largely, continues till today, despite much historical resistance … So, the lines between Sanskrit and Tamil had been drawn very sharply from that time itself,” Balachandran added.

The genesis of the Bhakti Movement is relevant in this context since, after Sanskrit became the language of the temples, the temple-going population began to dwindle, explained Balachandran. Moreover, the Pallava kings and the Pandian King Nedumaran, at the time, patronised Jainism, which also contributed to crowds dwindling at Shaivite temples.

“To encourage people to go to the temples, from the time of Mahendravarman [of the Pallava dynasty], who converted from Jainism to Shaivism under the influence of venerable Shaivite saint Appar, rulers began to patronise songs praising Shiva in Tamil,” he said.

From as early as the seventh century CE, the logic that there was a correlation between the Brahmin caste identity and the Sanskrit language, and the non-Brahmin Shaivite identity and the Tamil language, existed.

As Balachandran said: “Shaivism in the Tamil language became a weapon to attract people to temples, who had left them because of Sanskrit and Jainism.”

But how the latent Sanskrit-Tamil schism, which existed for centuries, transformed into a full-blown antagonism is the story of how colonialism overhauled existing social relations in Madras and how the British wrote the “definitive” history of the Tamil language.

Also Read: Chennai’s ‘metro man’ to one of Modi’s most trusted, TV Somanathan is more economist than generalist

A British discovery: The history of Tamil

Indians did not have an “intelligent, discriminating interest” in studying their languages, a British missionary and linguist, Robert Caldwell, declared in 1856 in his book, A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Family of Languages.

The “natives”, he in despair said, did not undertake a comparative study of languages, did not even know that such a thing as a “family of languages” existed, and certainly did not know the history of their languages.

The likes of Caldwell, in whose honour the first DMK government in the state erected a large statue in 1967 and whose house at Idayankudi in Tirunelveli district was turned into a memorial as recently as in 2012, took upon themselves to give a “history” to Indian languages, and most significantly, to the Tamil language.

Their histories came with clear distinctions and hierarchies. There was, according to them, a “Dravidian family of languages”, which purportedly included Tamil and other languages of South India, and the “Indo-European family of tongues”, which included, foremost and most significantly, Sanskrit.

As argued by Sumathy Ramaswamy in her book,The Passions of the Tongue: Language Devotion in Tamil India, Sanskrit, in this scheme of things, was a “classical tongue”, and Tamil a mere vernacular. Sanskrit was the language of the ‘fair’ and ‘noble’ Aryans, and Tamil was the tongue of the ‘menial’ and ‘dark-skinned’ Dravidians.

This discourse on language did not take place in a vacuum. Under British colonial rule, India was increasingly being imagined as primarily Hindu, and Hinduism as consisting of two primary streams—the “Aryan religion” found in Brahmanical texts in Sanskrit, and the “Dravidian religion” of the “aboriginals”, with no robust textual source, and therefore, considered “barbaric”.

“Fear-ridden”, “hideous”, and “wholly degrading, intellectually, morally and spiritually” are how, for instance, the Baptist missionary Wilber Theodore Elmore described the Dravidian religion.

Such was the “Aryan religion” valorisation and the disdain for the “Dravidian religion” that a 1912 Government of India document said, “Whatever be their present-day union or intermingle-ment, it is difficult to imagine any original connection of the Aryan Brahmans and their subtle philosophies with the gross demonolatry of the Dravidian peoples who surround them.”

Those who identified themselves as “Aryan-Brahmans” were ecstatic. In the British narrative, which they appropriated with gusto, they were the corrupted, whereas the Dravidians were the corrupters. To save Hinduism, the Brahmins only needed to go back to the uncorrupted Aryan-Brahminic texts, they started thinking.

A new life was slowly being breathed into the centuries-old schism between the “outsider” Sanskrit-speaking Brahmins and the Tamil-speaking locals. The latter, particularly the English-educated and -speaking among them, felt devastated.

In almost a single stroke, they stood dismissed as “inferior”, their influence labelled “hideous” and “corrupting”, their language reduced to the status of a “vernacular”, and their religion called “barbaric”, “irrational”, and “lacking scriptural foundations”.

The only way to challenge that discourse was a respectable history of Tamil or Dravidian religion, language and culture. And not accidentally, colonial and missionary writings provided the bare bones of this history.

The same Elmore who termed Dravidian religion as “barbaric”, for instance, also argued that it far preceded Aryan arrival all over India. The ancient Tamil society, he said, was egalitarian and uncorrupted by the oppressive caste system of the Aryans—a narrative lapped up by the upwardly mobile and English-educated Tamils. They started saying that they were “originally” civilised, and the Aryans later corrupted their monotheistic, rational, and casteless religion, Shaivism. To attain the lost Dravidian glory, they asserted, their religion and language required cleansing of its “polluting” Aryan and Sanskrit influences.

‘Tam-brahm’: The enemy within

In the South, if the Aryan Brahmins were the new enemy on a national level, the Tamil Brahmins, the “outsiders” of the seventh century, were the enemy within. While the Tamil Brahmins had, over the centuries, developed strong dependencies on the local landlord castes, the relationships began to strain under colonial rule.

As avenues of English education and modern professions opened, the dependence of Brahmins on the wealthy, landowning castes began to diminish. Be it law, medicine, education, or politics, the Brahmins, a minority of three percent in colonial Madras, were suddenly everywhere.

They asserted their religious and spiritual dominance in Sanskrit while also adopting English as their language under colonial rule. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, English-speaking Brahmins opened up the Theosophical Society, which started Sanskrit schools across different cities in Madras.

“Unlike in other parts of India, the Brahmins in Madras did not make strategic alliances with other upper castes,” said Balachandran. “They began to categorise all non-Brahmins as Shudras, thereby greatly offending the elite and landowning castes on whom they [Brahmins] had been economically dependent.”

Tamil, the language of the people, slowly turned into the “language of the Shudras”.

At the same time, Tamil, as the language of the non-Brahmins, was first becoming a core part of the then-newly shaping modern Tamil identity, which stoodin opposition to the English- and Sanskrit-speaking Brahmins.

The category of Tamil-speaking non-Brahmins, purportedly encompassing all people, however, was created and represented by the elites among the non-Brahmins. Like the Brahmins, they received an education in English and competed for jobs and prestige under colonial rule.

They sought to “elevate” Tamil to Sanskrit’s “divine” and ancient status by asserting that Tamil was the language of Shaivism and that the Aryan religion and Sanskrit had corrupted the Dravidian religion and Tamil.

On the political front, a group of nationalists from the Madras Presidency, hitherto with the Indian National Congress, came together and published the “Non-Brahmin Manifesto” and formed the Justice Party in 1916.

Indians were not ready for self-rule, the manifesto declared. If the Indians were granted independence, it would lead to nothing but the tyranny of the Brahmins over others. Through books and journals, religious and Tamil classes, conferences, and local libraries, the non-Brahmin elites captured the modern public sphere of Madras as never before.

By then, Tamil had ceased to be inanimate, with the language elevated to a status upholding the political, religious and social identity of Tamilnad—the land of Tamil.

But, a problem remained. The elites were still making the assertions, and their preoccupation with making Tamil a language of Shaivism was still far removed from the lives of ordinary Tamilians. How could the movement for Tamil exit the chamber halls and reach the streets?

Enter E.V. Ramasamy Naicker, or Periyar.

Periyar: Making Tamil a people’s language

Balachandran said that the social composition of the Justice Party was very elite. “They were, after all, the zamindars, who were exploiters of the Shudras in their own right,” he said. “But, to challenge the might of the Brahmins, they created a category and became its spokesperson.”

Balachandran also said the Justice Party, for sure, did a lot for social justice after coming to power in the Madras Presidency in 1920, introducing reservation, for instance, to break Brahmin hegemony in government jobs.

But their preoccupations with religion and Tamil were elitist, he said. The Hindu Endowment Act, which gave the government control over Hindu temples, for instance, was introduced by the Justice Party largely to seize control of temples from Brahmins, he added.

Even the Tamil they used was a purist, sanitised version of the language—alien to ordinary Tamilians, Ramaswamy wrote in her book.

For Periyar, an atheist and a member of the Justice Party, neither its politics nor its language, therefore, represented the oppressed.

As argued by A.R. Venkatachalapathy in his book Tamil Characters: Personalities, Politics, Culture, the language of the non-Brahmin movement until the 1920s was English or a highly stylised and sophisticated Tamil.

Periyar changed all that. He did not just despise Sanskrit. He equally despised the “Sanskritisation” of Tamil. For him, Tamil was not divine or an object of devotion but the language of people, regardless of class, caste or racial identity. In that context, he called the language “barbarian”, as referenced by Sitharaman in the Parliament last month.

In line with his thoughts on Tamil, Periyar disapproved of the scholarly focus on traditional texts and not on conveying scientific knowledge in Tamil, as had successfully been done in English. He criticised Tamil for “clinging to ancient glories” without adapting to modern needs.

Periyar—using tales, similes, illustrative stories, proverbs, and popular sayings of ordinary Tamilians—not only changed the status of Tamil but also the social composition of “non-Brahmins” in Tamil Nadu forever.

As Venkatachalapathy said: “Arguing that the Shudra status of non-Brahmins would not be wiped out until the varna category [of Dalits] was annihilated, he asserted that Dalits had an unconditional claim over every advance that the non-Brahmin movement made.”

Thus, Periyar transformed the Tamil identity from an elite non-Brahmin identity to a mass, non-Brahmin identity, mobilising dozens of barely-educated men such as Chinnaswamy to give up their lives for its cause.

“Such was the power of the Tamil Renaissance in the 1920s that there came a time when people would even name their children as Tamil,” lawyer and DMK leader Manuraj Shunmugasundaram told ThePrint. “It is unimaginable that someone is named Hindi or Malayalam … but because Tamil is seen as the cornerstone of Tamil identity way more than religion or caste, this is possible among Tamil speakers—it is their No. 1 identity marker.”

The unabashed Hindutva politics of the BJP is bound to trigger the existential anxieties of Tamils, given that Tamil is not just a language but encompasses within it the long political, caste and religious struggles of its speakers, Balachandran explained.

“If Tamils believe that their status in the nation is under threat under the BJP, it is because the BJP government triggers these historic wounds of identity,” said Balachandran. “Today, a disproportionately large percentage of bank employees in Tamil Nadu are Hindi speakers. That never happened under the Congress rule … For Tamilians, of course, such moves are an insidious way of changing and homogenising Tamil culture itself.”

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also Read: Jallikattu begins today — the ‘barbaric sport’ that celebrates hard-working Tamil farmer